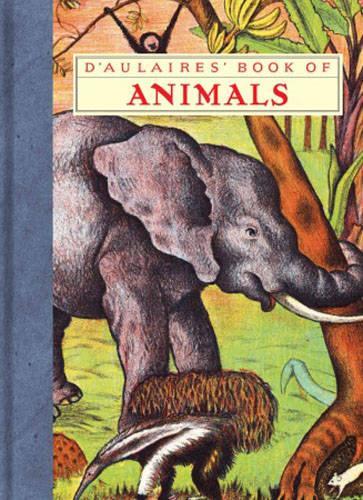

D'aulaires' Book Of Animals

(Paperback, Main)

Publishing Details

D'aulaires' Book Of Animals

By (Author) Ingri

New York Review Books

NYRB Children's

15th March 2013

Main

United States

Classifications

Children

Fiction

590

Physical Properties

Paperback

30

Width 215mm, Height 287mm, Spine 12mm

505g

Description

D'Aulaires' Book of Animals introduces young children to the creatures of every continent. Here more than fifty animals lithographed in full color form one side of a book that can be read page by page or unfolded to form a continuous panorama; the flipside of the panorama reveals the nighttime world of the animals in the very same settings. Each tableau presents the subjects in their native environments-from the tropical to the arctic-and is rendered with the exemplary richness of color and delightful understanding of the children's world that distinguish the d'Aulaires' much-loved retellings of the Norse and Greek myths and their wildly playful Book of Trolls. Young children, meeting animals from all over the world for the first time, will be delighted not only with the animals themselves but with the simple and engaging text which provides information about the way they act, the world they live in, and-best of all-the sounds they make. D'Aulaires' Book of Animals is not only a perfect picture book for preschoolers, but a work of art that can be enjoyed by all.

Reviews

"Unfold this glorious eight-foot-long frieze of nature's wild things and share a round-the-world safari with your favorite young animal lover. First published in 1940 and now happily back in print." -Parenting Magazine

"Those familiar with D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths will appreciate the New York Review Books' efforts to unite the authors' backlist. Having reissued both D'Aulaires' Book of Norse Myths and D'Aulaires' Book of Trolls , the publisher now presents the paper-over-board D'Aulaires' Book of Animals by Ingri and Edgar Parin D'Aulaire, originally published in 1940 as Animals Everywhere. The book folds out into a glorious full-color landscape, stretching from jungle to desert to Arctic climes; the reverse side, in b&w, names the animals and the sounds they make." -Publishers Weekly

Author Bio

Ingri Mortenson and Edgar d'Aulaire met at art school in Munich in 1921. Edgar's father was a noted Italian portrait painter, his mother a Parisian. Ingri, the youngest of five children, traced her lineage back to the Viking kings. The couple married in Norway, then moved to Paris. As Bohemian artists, they often talked about emigrating to America. "The enormous continent with all its possibilities and grandeur caught our imagination," Edgar later recalled. A small payment from a bus accident provided the means. Edgar sailed alone to New York where he earned enough by illustrating books to buy passage for his wife. Once there, Ingri painted portraits and hosted modest dinner parties. The head librarian of the New York Public Library's juvenile department attended one of those. Why, she asked, didn't they create picture books for children The d'Aulaires published their first children's book in 1931. Next came three books steeped in the Scandinavian folklore of Ingri's childhood. Then the couple turned their talents to the history of their new country. The result was a series of beautifully illustrated books about American heroes, one of which, Abraham Lincoln, won the d'Aulaires the American Library Association's Caldecott Medal. Finally they turned to the realm of myths. The d'Aulaires worked as a team on both art and text throughout their joint career. Originally, they used stone lithography for their illustrations. A single four-color illustration required four slabs of Bavarian limestone that weighed up to two hundred pounds apiece. The technique gave their illustrations an uncanny hand-drawn vibrancy. When, in the early 1960s, this process became too expensive, the d'Aulaires switched to acetate sheets which closely approximated the texture of lithographic stone. In their nearly five-decade career, the d'Aulaires received high critical acclaim for their distinguished contributions to children's literature. They were working on a new book when Ingri died in 1980 at the age of seventy-five. Edgar continued working until he died in 1985 at the age of eighty-six.