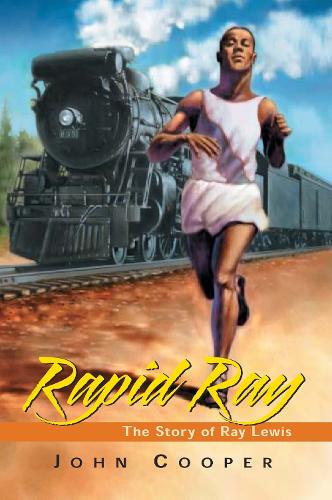

Rapid Ray: The Story Ray Lewis

(Paperback)

Publishing Details

Rapid Ray: The Story Ray Lewis

By (Author) John Cooper

Tundra Books

Tundra Books

15th May 2011

Canada

Classifications

Children

Non Fiction

B

Physical Properties

Paperback

160

Width 131mm, Height 194mm, Spine 8mm

163g

Description

Rapid Ray Lewis was arguably the fastest man of his generation. He won medals in the 1932 Olympics and the 1934 British Empire Games, and countless races in North America. Remarkable achievements for any man - but all the more remarkable because Lewis had to race poverty and prejudice. The geat-grandson of slaves, he worked as a porter on the railway, and trained by running alongside the tracks when the train was stopped on the prairies. Rapid Ray is far more than a sports autobiography; it is as much a history of one man's battle for equality as it is a history of Olympic-level track. Throughout his long life - he is now in his nineties - Ray Lewis has fought discrimination not only in sports, but in every walk of life. Excerpt Chapter 1- My Early Years My name is Raymond Gray Lewis. Most people just call me Ray. But there was a time when just about the only name I was known by was Rapid Ray, in my hometown of Hamilton, Ontario, and across Canada. Why was I called Rapid Ray Because I could outrun just about any other opponent when I was young. Of course, I was called a lot of other names too, mostly because of my skin color. Being a Canadian of African descent, I grew up during a time, in the early part of the 20th century, when being black meant that you were treated differently than people with light skin. It was a time of terrible discrimination. You had to struggle. You might have to fight hard for a job. You could expect to be turned down for a loan from a bank if you were trying to buy a house. In school, you were likely to be teased or called names by your classmates - and the white teachers might treat you poorly - all because of the color of your skin. Even just buying a loaf of bread at the grocery store, getting a table in a restaurant, or trying to sit in the front section of a movie theater could be difficult. Black people in Canada and the United States, the descendants of slaves brought to work on farms and plantations, had to fight for respect every day of their lives. As the great-grandson of former slaves, it was no different for me. I had to put up with all kinds of name calling, by other kids and later by adults, whether I was running to school, racing around the block, or competing in track-and-field meets across the country. But you can believe me when I tell you that being treated poorly by others didn't defeat me. It only made me want to run harder, to prove to everyone that I could achieve great things. I ran so hard, in fact, that I went all the way to the Olympic Games in Los Angeles, California, and to the British Empire Games in London, England, where I even sat down to dinner with royalty. While I was training as an athlete for the Olympics, I worked hard, too, as a railway porter on the Canadian Pacific Railway, serving people who were traveling across Canada and into the United States. I was born in Hamilton, on Clyde Street, on October 8, 1910. Hamilton is known as Canada's Steel Town, and it produces much of the steel used in manufacturing things we use every day, from cars and stoves to refrigerators, tools, and machinery. It was - and still is - a very busy city. I grew up watching cargo carriers steam into the harbor with raw iron ore; people bustled about the streets to and from work, and horses pulled wagons that carried milk, eggs, and bread to customers throughout the city. I was the youngest child of Cornelius and Emma Lewis. My eldest brother was Victor, followed by my sister Marjorie, then my brother Howard, and finally me. My parents taught me the value of working hard. That meant working hard in school and, when I became an athlete, training hard too. I attended Wentworth Street Public School. I used to get up in the morning, have my breakfast, and, while I didn't dawdle too much, sometimes I had to run hard to get to school before the bell at nine o'clock a.m. Lucky for me, the school was only about a block and a half away. I'm pleased to say that I was never late to school, not even one day, even though I had to run hard to get there at times. It was a big public school for the time - two storeys high, with several hundred students and more than twelve rooms. Many years after I attended it, Wentworth Public School was closed and later torn down to make way for an apartment building. Growing up on Clyde Street was fun. The younger I was, the less fuss white people made about the color of my skin. My friends and I used to play hockey on the streets and, where buses, cars, and trucks now drive through Hamilton's busy downtown core, the milkman and the bread man would come down the street in their wagons, pulled by big, strong horses, clip-clopping along at a slow but steady pace. On Friday nights, the farmers would come up nearby Cannon Street, their horse-drawn wagons loaded with produce, heading for the market that opened on Saturday morning. In those days before refrigerators, the ice wagon was another sight, trundling down the street, delivering huge blocks of ice. The iceman was big, with broad shoulders and thick, ropy arms. He'd use long iron tongs to grab a block of ice, then sling it over his shoulder to make his delivery, whistling as he headed into one of many houses that had an icebox. Once in a while, kids would swipe a peach or other piece of fruit from a passing farmer's wagon. Police officers, patrolling the downtown neighborhood on bicycles, would chase the rascals through the streets, but the kids usually got away. While some people owned automobiles, they were expensive and were rare sights. Most people got around by walking or on bicycles, or they used the streetcar. When I was growing up, streetcars were a familiar sight along what was called the Belt Line, which ran through Hamilton's downtown core. And just two blocks from my house was the car barn where streetcars were repaired. My friends and I would watch the streetcars being moved around in the big yard where they were stored. We would watch and marvel at the mechanics working on the big streetcar engines. Just down the street from my house was the fire hall. My friends and I might be playing in Woodland Park, not far from my home, and hear the siren of the fire wagon as the firefighters took off, slapping the reins of their horses in response to a call. That was a call to us too. We dropped our gloves and bats and took off towards the station. We would run alongside the horses as they charged out of the firehouse. We could run as fast as the hook-and-ladder wagon for about 50 or 60 metres, even taking off ahead of them for a while. I would always be out in front of my friends, almost nose to nose with a big bay mare, hearing the huffing of her breath as the firefighters urged her on. I would listen to the sound of the horses' hooves pounding on the street before they would pick up their pace and canter off ahead of us up the street, leaving us to catch our breath in the dust they stirred up. I ran everywhere. I would run past the train station and see the passengers boarding or disembarking, and the porters, all of them black like me, stooping to pick up bags or to help people onto the train - always smiling, always polite. During the week, I would have to run over to Barton Street to get coal oil for our family's lamps. Like a car, electricity was an expensive commodity, and it would be a few years before we could afford to have electricity put into our house. For kids, watching sports, as well as playing them, was a great way to have fun, and Hamilton in those days was home to many great sports teams, like the Hamilton Tigers of the NHL. The Hamilton Tigers hockey team would play against Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal at the Hamilton Arena, which was owned by the Abso-Pure (for "absolutely pure") Ice Company, at the corner of Wentworth and Barton Streets. Not only did the company sell ice - it ha

Reviews

While sports fans will find the story eminently readable for its tale of victory, theyll also find here a depth of wisdom thats not usually associated with sports writingThis is a rewarding read and, with a chronology and index, its a most welcome and much needed addition to black Canadian history for children.

Deirdre Baker, The Toronto Star

it is fascinating to read about Lewiss experiencesRapid Ray is definitely worth reading.

Canadian Childrens Book News

Author Bio

John Cooper is a corporate communications specialist for the Government of Ontario. He also teaches corporate communications at Centennial College in Toronto, and writes books. John has been interested in African-Canadian history since he was 12 years-old when he read Black Like Me. He is a member of the Urban Alliance on Race Relations, and is editor of their newsletter. John Cooper first wrote about Rapid Ray Lewis in his adult book, Shadow Running. He also co-wrote and edited My Name's Not George. Rapid Ray- The Story of Ray Lewis is a book for younger readers which is both a social history and a book about running. John Cooper lives in Whitby, Ontario with his wife and three children.